Edit: This post is now very out of date! See version 3+ of the paper for a new approach.

Myself, my Newcastle colleague Colin Gillespie and our PhD student Sophie Harbisher recently uploaded a second version of a paper to arxiv. I thought this would be a good opportunity to blog about it while it’s fresh in my mind. The paper is on Bayesian experimental design, and how to scale it up to higher dimensional problems at a reasonable cost. In this first blog post I’m going to describe our method. Then in a second part I’ll explain some of the theory behind it.

You can also have a look at our code for this project on github.

Design of experiments

Before collecting some data we can often make some choices about how to do so. This can affect how informative the results are, and how expensive the collection process is.

The classic setting, from which the statistical terminology is taken, is where a design is selected before performing an experiment. Applications include:

- How many patients to use in a clinical trial.

- When to take measurements in a physics/biology experiment.

- Where to performing sampling in statistical ecology.

Similar settings also appear whenever a decision must be made about how to collect data for making a future task e.g.

- Where to place sensors in an autonomous vehicle.

- Where to evaluate a function for numerical integration.

- What parameter settings to use for runs of expensive climate simulators.

So classical design of experiments has a strong overlap with modern tasks in machine learning (e.g. active and reinforcement learning), probabilistic numerics and uncertainty quantification.

Design of experiments (DoE) has a long history in statistical research. The classic approach dates back to at least R A Fisher’s work in the 1920s-30s. In modern applications, it’s increasingly feasible to collect large amounts of data, so there’s an increasing emphasis on being able to select high dimensional designs.

Technical setup

We focus on the continuous version of DoE. That is, we wish to select a design made up of a fixed number of continuous quantities. For example we could be selecting measurment times, measurement locations, dose sizes etc. Mathematically we wish to select a \(d\) dimension vector \(\tau \in \mathbb{R}^d\).

We look at Bayesian experimental design, which uses the following decision-theoretic framework.

- The experimenter must select a design, \(\tau\).

- Nature selects some parameters, \(\theta\). We assume these are generated from a prior distribution \(\pi(\theta)\). (The parameters are unseen by the experimenter.)

- Nature generates some data \(y\) based on \(\tau\) and \(\theta\). We assume this is generated from a model with likelihood function \(f( y \mid \theta; \tau)\). (These are seen by the experimenter.)

- The experimenter receives a utility, \(\mathcal{U}\) depending on \(\tau, \theta, y\) (or a subset of these).

To use this framework we have to make assumptions about how nature produces data i.e. select a model and its likelihood function. The model typically depends on some unknown parameters \(\theta\). In a Bayesian approach we have to make assumptions their distribution i.e. select a prior. (Classic non-Bayesian DoE approaches face a similar issue, as they require picking a single nominal parameter value at which to assess the design.)

In Bayesian DoE, the optimal design is that maximising the expected utility (with respect to parameters and data). The computational challenge is to solve this optimisation problem - or come up with a close approximation - in a reasonable time.

Utility functions

The utility function \(\mathcal{U}\) is an important choice in DoE. It describes how useful the outcome is to the experimenter, taking into account both costs and benefits. Ideally a utility function could be designed for the particular application at hand. But this is often not possible and a generic utility function is used instead. This aims to measure how informative the experimental results are.

Most generic utility functions for Bayesian DoE involve the posterior density \(\pi(\theta|y;\tau)\) i.e. the distribution of the parameters given the design and data. The posterior summarises the experimenter’s knowledge of the parameters at the end of the experiment. The utility can be taken to be some scalar summary of the posterior - or the posterior compared to the prior - which describes how much information has been gained. Chaloner and Verdinelli, 1995 and Ryan et al, 2016 review many possible choices.

Computational challenges and existing methods

Calculating the posterior is typically computationally expensive. This makes Bayesian DoE challenging: we want to optimise expected utility but:

- We can only evaluate a single utility at a time, not its expected value.

- Even a single utility evaluation is expensive!

Many methods have been proposed for Bayesian DoE, including:

- Optimisation using MCMC, using Peter Müller’s algorithm.

- Coordinate ascent using Gaussian process optimisation, using the ACE algorithm of Overall and Woods.

- Approximating the expected utility by variational inference, using recent work of Foster et al.

However these all involve computational expense and/or approximations.

The FIG utility

We propose using a particular utility function which can be evaluated without posterior calculations. This makes the optimisation problem much simpler and cheaper, as we’ll see shortly.

We use what we call the Fisher information gain utility, \(\mathcal{U}_{\text{FIG}}(\theta, \tau)\). This is the trace of the Fisher information matrix. (As used in the non-Bayesian T-optimality criterion.) The Fisher information matrix is often available in closed form. Even if not, an unbiased Monte Carlo estimate can be formed in many applications (see Appendix E of our paper). In both cases it’s not necessary to infer the posterior.

Utility functions which avoid in the posterior in this way have been criticsed as being pseudo-Bayesian for not using the full information available from the data. However Stephen Walker recently showed that it turns out this utility produces the same optimal designs as a fully Bayesian utility (i.e. one which is a posterior summary). Our paper extends this argument by giving a foundational Bayesian derivation of the FIG utility through decision theory. The details are in the second part of this blog post.

Optimisation

We wish to maximise our expected utility,

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{J}(\tau) = E_{\theta \sim \pi(\theta)} [\mathcal{U}_{\text{FIG}}(\theta, \tau)]. \end{equation}\]We usually can’t evaluate this expectation. However we can compute an unbiased Monte Carlo estimate of its gradient,

\[\begin{equation} \widehat{\nabla_\tau \mathcal{J}(\tau)} = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K \nabla_\tau \text{tr} \mathcal{I}(\theta^{(k)}, \tau). \end{equation}\]where

- The \(\theta^{(k)}\)s are samples from the prior.

- \(\nabla_\tau\) represents gradient with respect to \(\tau\).

- \(\text{tr}\) represents trace.

- \(\mathcal{I}\) is the Fisher information matrix.

(Some regularity conditions are needed to allow swapping the order of expectation and gradient. Also the above is for the case where the trace of the Fisher information is easily differentiable e.g. using automatic differentiation. See our paper for more details.)

We can now use a powerful off-the-shelf method - stochastic gradient optimisation. We produce a sequence of \(\tau_i\) values where \(\tau_{i+1}\) equals \(\tau_i\) plus a step in the direction of \(\widehat{\nabla_\tau \mathcal{J}(\tau_i)}\). These converge to a local maximum of \(\mathcal{J}(\tau)\).

Lots of powerful adaptive stochastic gradient optimisation methods have recently been developed in the machine learning literature. They are typically used for learning the parameters of neural networks, and so can handle upwards of millions of unknowns. So we simply use the popular Adam algorithm for optimisation.

To summarise, we are in the nice position of simply applying standard gradient based optimisation to an easily available gradient estimator of our objective function \(\mathcal{J}\). In contrast, under most other utility functions, evaluating the objective function or its gradient is much more computationally demanding, and can necessitate using specialised optimisation algorithms or introducing approximations.

Example: geostatistical regression

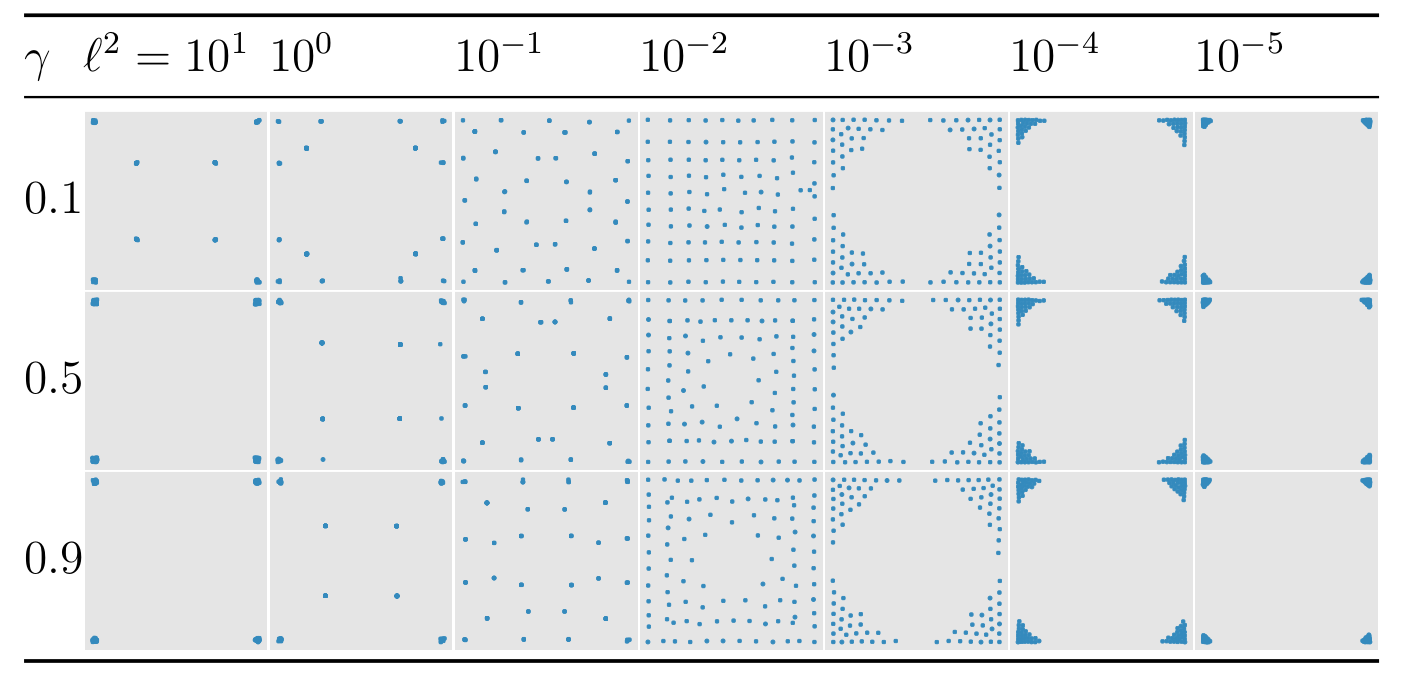

Our paper contains an application to geostatistical regression. We are collecting spatial data assumed to follow a Gaussian process model with linear trends which we wish to learn about. Our method can find optimal designs of 100 locations in under a minute. The following figure shows some of the designs under various GP parameter choices. (See the paper for more details.) These show an interesting mix of regularly spaced points or concentration near the corners.

Difficulty 1: reparameterisation and weighting

One difficulty of our approach is that the Fisher information matrix is not invariant to reparameterisation, and therefore neither is our utility function. That is, simply by working with our parameters on different scales, we can end up with different designs. This is not a desirable property!

To deal with this we work with a weighted utility function. Our original utility function is the sum of the diagonal elements of the Fisher informatoon matrix. The weighted version instead uses a weighted sum of these elements. We propose an algorithm to adaptively select the weights so that we learn a similar amount of information on each parameter.

Difficulty 2: repeated design points, local maxima and post-processing

Another difficult of our approach is that it converges to local maxima of the expected utility rather than the desired global maximum. We found this particularly problematic in one example - see Section 6 of the paper. Here the designs represented a vector of times at which to make observations. Our optimal designs turned out to select repeated observations at two particular time points. Over multiple runs of our optimiser, there was considerable variation of how many design points were placed at each of these two times i.e. these outcomes formed many local maxima.

To deal with this we recommend post-processing our output if there are repeated points. We use the “ACE phase II” post-processing method implemented in the R package for ACE. This performs combinatorial optimisation by moving design points between replicated groups.

Whether or not there are repeated design points, we always recommend running our method multiple times from multiple starting designs. This checks for multiple local maxima.

It’s unclear whether repeated design points should be regarded as problematic or not. For example Binois et al recently argued that replicated observation times can be highly informative. Alternatively the tendency for replication in this example could represent some undesirable features of the utility function. I’ll discuss this further in the second part of this blog post.

Future research directions

We’ve used off-the-shelf stochastic gradient optimisation methods to allow fast Bayesian optimal design which can scale up to higher dimensional designs than most existing methods. These optimisers are typically designed for neural network applications. It would be interesting to see if variants can be designed specifically for experimental design. For example these could try to escape local maxima using tempering or line search.

Also all our examples were for fully observed models. The required Fisher information calculations are harder for models with latent/nuisance variables. Extending our method to this setting is another interesting possibility.